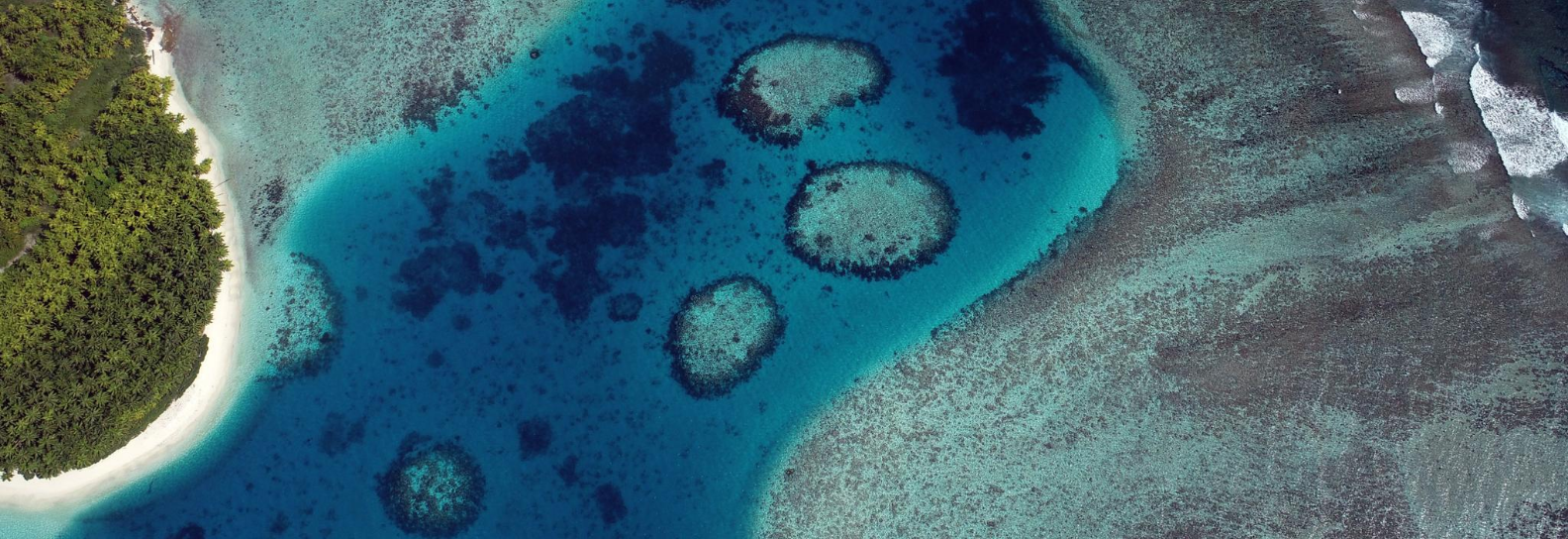

At the end of June 2019 I was on a tiny, remote island in the middle of the Indian Ocean, surrounded by turquoise ocean and blue sky. The middle of the island was covered in lush vegetation and the edges, in white sand. It was certainly one of the most beautiful places I’d taken my trusty refillable bottle to!

I wasn’t alone though. I was with a small team of fellow scientists, and a gang of enthusiastic volunteers. And we spent the afternoon picking up plastic. A lot of plastic. We spent two days carrying out beach surveys, documenting all the plastic we found, logging over 7,000 individual items.

The ZSL, Swansea, BIOTA and Deakin University scientists with the beach clean volunteers © ZSL

On the afternoon of the second day we paused our scientific surveys and spent three hours collecting as much of the plastic beach waste we could get our hands on. We filled up 50 bags, each with a 200-litre capacity, with plastic rubbish. Polystyrene and plastic fragments, flip flops, food containers, fishing gear, and many other items, including… you guessed it – bottles. Hundreds of them. We collected 804 water bottles in three hours that afternoon before we ran out of time and had to head back to the boat. We wish we’d have had the time and power to collect all of the nearly 2,000 bottles – both water and other beverages – that we surveyed on that island.

Bottles on the beach on Iles des Rats (so many bottles in just one small square!) © ZSL

We were on Ile des Rats Island in the Egmont Atoll; one of the 58 islands that make up the Chagos Archipelago. Like 56 of the other islands in the archipelago, Ile des Rats is uninhabited and extremely remote. It took us around eight hours to travel there by boat from the only inhabited island in the archipelago, Diego Garcia (DG).

So where were all of these plastic bottles coming from? We were able to determine the country of origin of 403 of the bottles by squinting in the sun at their labels and branding. The rest were label-less and quite often battered by the ocean, so it was impossible to tell. Of these 403, we counted bottles from 17 different countries, with the top five being Indonesia, China, Maldives, Malaysia and Sri Lanka.

Using the labels to determine where the bottle might have come from © ZSL

The volume of plastic we found was bad enough but something else made it worse. Another very noticeable thing about the island we were on was the large, crater-like holes in the sand right up by the vegetation, accompanied by big tracks to and from the shoreline. Turtle tracks. This island, like many others in the Chagos Archipelago is where two species of sea turtle come to nest; the endangered green turtle and the critically endangered hawksbill turtle. And this is one of the reasons we were there.

As part of a new Darwin-funded project, we were – and are – seeking to understand and mitigate the negative impact of plastic beach waste on turtles. We know from other studies that plastic can hinder sea turtle nesting; physically getting in the way of nest excavation, affecting the conditions in the nest by changing the temperature and humidity of the sand, presenting a physical barrier when hatchlings emerge from the nest, and be mistaken for food.

We’re also trying to work out how much plastic is accumulating on these beaches, where it’s coming from and how quickly it accumulates there. This is all further data that will help us to understand the scale of the problem we’re dealing with and how best to tackle it.

Back on DG, we took the 50 sacks of plastic we’ve collected and transported back by boat and emptied the contents onto a growing pile of rubbish collected from beaches, at the waste management site. It was disheartening to see this enormous pile of mostly plastic waste – but unfortunately DG is suffering the same fate as the smaller island we’d just visited. Swathes of plastic waste also wash up on DG’s shores, and it’s through the efforts of volunteers that the beaches are cleaned and the litter transported to the waste management facility. Another piece of the puzzle is what to do with this plastic waste – can we transform it into something useful? This is something we’re also investigating through our work.

Fiona Llewellyn (ZSL) and teammate, Jacques Laloe (Deakin University) with the 50 bags of plastic waste collected © ZSL

This is a project with lots of questions, lots of research needs and lots of action that needs to be taken.

We’re working with the territory’s Administration, and the people that live there, to help them ‘go #OneLess’ and stop using single-use plastic water bottles themselves. The tap water on DG is drinkable, so we’re taking an adapted version of our London-focused #OneLess campaign to DG and encouraging them to make the switch from plastic bottled water to refilling instead.

Our end goal of course is to prevent the plastic from entering the ocean and washing up on the shores of the Chagos Archipelago in the first place, harming and hindering wildlife. It’s a global problem for shorelines everywhere. But it’s also something we can all play a part in through reducing our own use of single-use plastic everywhere.

Love your refillable bottle and say no to single-use plastic water bottles. For the love of turtles, and the ocean.

Fiona and ZSL teammate, Emma Levy – hot and sweaty work – but a cleaner beach in the background! © ZSL

The project team are:

- Rachel Jones, Fiona Llewellyn and Emma Levy (ZSL)

- Harri Morrall and Nadine Atchison-Balmond (BIOTA)

- Nicole Esteban (Swansea University)

- Jacques Laloe (Deakin University)

The project, Reducing the impacts of plastic on the BIOT natural environment, is funded by the Darwin Initiative

For more information on this project, visit https://www.darwininitiative.org.uk/project/DPLUS090/

Our project partners are: